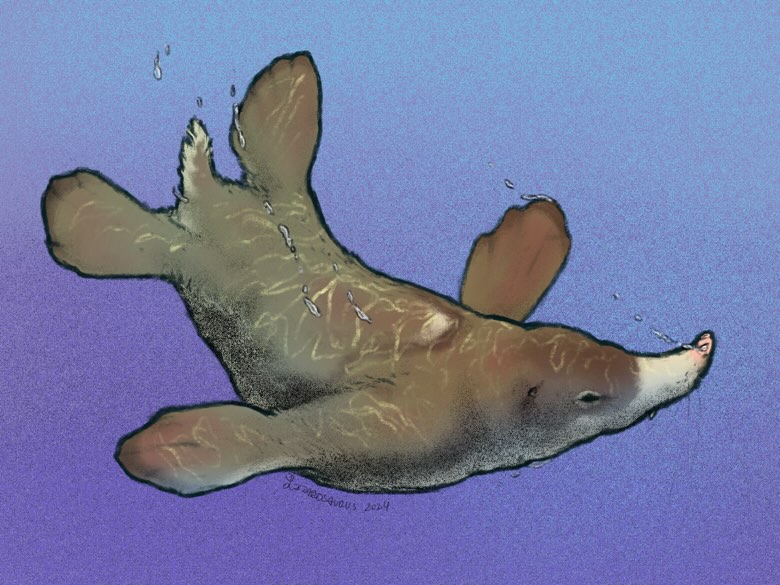

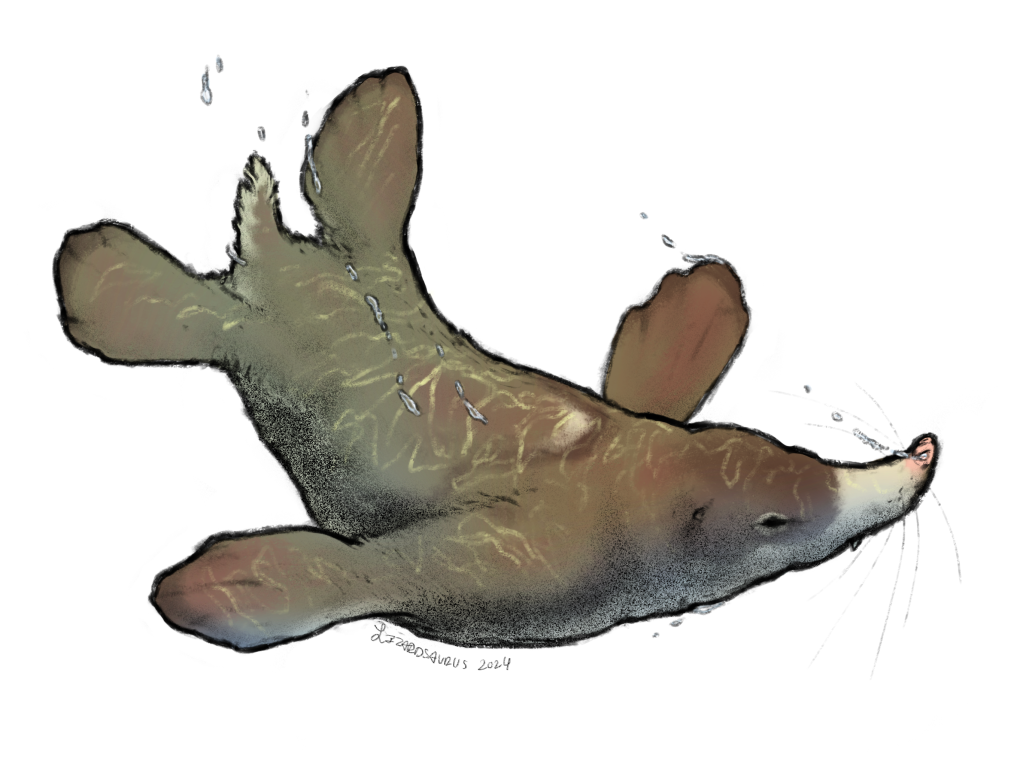

Illyriolestes piscimimus, a freshwater dryolestoid from european waterways during the Oligocene. By lizardsaurus.

The Iberian Peninsula is an odd player across the history of the Mesozoic and Cenozoic. It served as a land bridge between Europe – and by extension Asia and North America – and Africa – and by extension the southern continents as a whole – bringing in abelisaurs and pleurodire turtles to Europe and various mammal groups to Africa on the other, among many other examples. Its days as a land bridge came to end towards the Eocene, however; a few land bridges still allowed some faunal interchanges with Africa, like terror birds in both timelines and galulatheriid gondwanatheres, but Europe became by and large an island continent. With the arrival of the Oligocene, the Grand Coupure saw to it as an extension of Asia, becoming thus a formed Eurasian continent alongside the also annexed Balkanatolia, with a connection to Africa only reestablished much later in the Miocene.

The fauna of the Iberian Oligocene is largely uniform with that of Asia, though hints of geographical isolation in this subcontinent give it its own unique spin. Gondwanatheres are by far the dominant herbivores, but in contrast to Asia and especially North America there is only one adalatheriid genus, the giraffe sized Berobreus longicollum, a tall and gracile browser. By contrast, the dominant herbivores are sudamericids, known by at least 44 genera ranging from the guinea pig sized Kontebria to the elephant sized Barochania asidia, an animal built much like a ground sloth and also found as far east as Mongolia. Lambdopsalids are also present, across various niches such as small rat-like generalists, hare-like sprinters and forms as large as a camel, but they are decidedly outnumbered by the local sudamericids, with only 23 genera in the Oligocene.

Most curious is a lower jaw from the Tagus Basin, which appears to belong to a meniscoessid. Similar scant remnants have also been found in other parts of this clades former kingdom in Balkanatolia, but if correctly inerpreted this represents a westernmost extent of this lineage, otherwise seemingly wasting away in marginal niches.

The most common local herbivore, however, is the pig-sized aquatic taeniolabidid Treposiren natans, a freshwaer species filling an ecological niche somewhere between a sea cow and a carp. They represent up to 80% of all fossils in the Tagus Basin and regionally on several other river systems; as the climate increases towards the end of the Oligocene and sea levels rise other taeniolabidids become rather common as well, including a much larger descendent species, Treposiren ebra, reaching as much as 7 meters. The earlier species are a case of freshwater dwarfism, occupying the niches vacant by several herbivorus fish families, while latter ones benefited from marine environments as sea levels rose. For taeniolabidids, evolution certainly is a zig-zag between fresh and salt water.

Compared to other parts of Eurasia, Iberia was wetter, having developed a forest environment not quite like the tropical rainforests of the Eocene, an early form of the laurassilva temperate rainforests. This may explain the odd predominance of sundamericids and freshwater taeniolabidids, while steppe dwelling adalatheriids and lambdpsalids were rarer. The old European forest endemics were long gone, but the canopies were dominated by various arboreal eucosmodontids, hopping like deranged tree kangaroos, and flying ptilodontoideans and dryolestoids, alongside various coliiform bird lineages, occupying niches ranging from analogous to passerines to raptors. An flightless ptilodontoidean, Endovelicus belles, is of an uncertain affinities: a cat-sized arboreal carnivore, it has features similar to afroptilodontoideans, namely the loss of a vestigial plagiaulacoid in front of the main one, but otherwise more closely resembles the North American Ectypodus.

The dominant carnivores are microcosmodontids as in the rest of the northern landmasses, ranging from weasel-like forms to the massive Runesocecius ibericum, a tiger sized predator with saber-like lower incisors. Some eucosmodontids are present as cat-like predators, but otherwise the only other predatory mammals are small shrew-sized remains inferred to be from kogaionids.

Insulonycteriids are represented by three genera, Magec ranging from 1.4 to 3 meter wingspans, the more robust Neito sylvopteryx with a wingspan of four meters and the massive Reve oilam with a wingspan of six meters. The former appear to have been generalistic carnivores like seagulls, occuring in both marine and terrestrial sites, while the latter is an unusual forest predator, bearing broad and shorter wings than normal for this clade, an unusual competitor for the large microcosmodontids. The last was a pelagic animal, and occurs only in coastoal sites. Acamapichtliids are to date only represented by a single semi-complete left wing, comparable to the cosmopolitan genus Yunzel. Alive, the animal likely had a four meter wingspan, large but not as massive as its contemporaries elsewhere.

The coastoal sites have a large variety of marine mammals and choristoderes. Besides the aforementioned taeniolabidids, one dagontheriid, Micronodens fututor, is a very common occurence in freshwater sites, an animal vaguely similar to an otter but with a tail fluke, primarily a carnivore but also capable of sieving crustaceans and aquatic insects thanks to the grooves in its plagiaulacoid. The monotreme Eurotrematum minor and the necrolestid Illyriolestes piscimimus also appear to have occupied similar carnivorous lifestyles in the freshwater ecosystems of Iberia, both four flippered swimmers; the former was about as large as a pike while the later was desman sized. They attest to the general tendency of Oligocene aquatic mammals displacing teleosts in costoal and freshwater habitats, which are nonetheless represented by various small perciform taxa. The waterways were truly ruled by Crouga dercetius, a six-meter long choristodere; by the end of the Oligocene and influx of marine predatory mammals and choristoderes displace these earlier forms, unlike the taeniolabidids. Alligatorids, turtles and Tomistoma false-gharials are also known.

From a landbridge to an island to a strange part of a greater whole, the Iberian Peninsula in the Oligocene demonstrates a bigger trend made twisted by partial isolation, the very confines of the Panarctic Empire.

Leave a comment