(As with all animal pages so far, this only goes so far into the Miocene… for now)

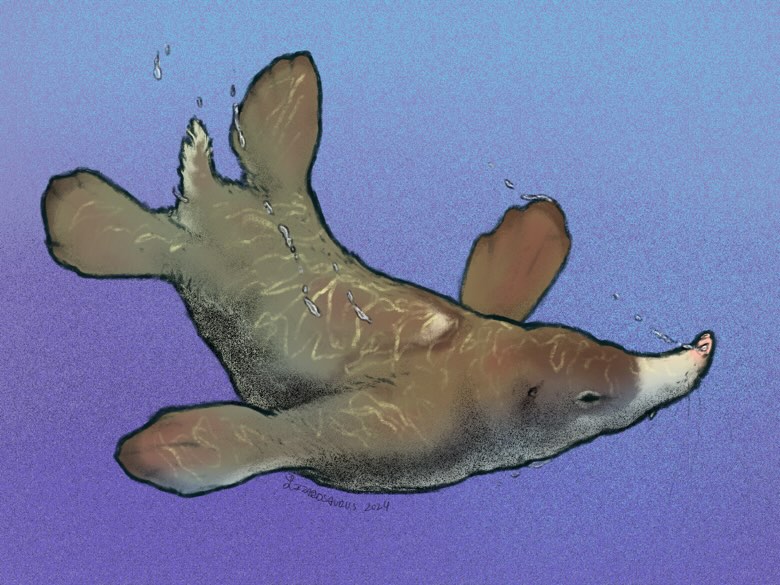

Iqiqquq by corvarts. The first marine mammal of this timeline, and though short lived it had the longest lasting impact.

As with our timeline, mammals took to the seas, exploiting the niches left vacant by Mesozoic marine reptiles as well as to exploit the abundant resources of the sea. As early as the Paleocene some taeniolabidids began to comb the beaches, in a manner much similar to our world’s pantodonts. Indeed, such behaviours might have allowed the group as a whole to survive the PETM, which was stressed for terrestrial mammals.

Soon after came the first true, fully marine mammal, the taeniolabidid Iqiqquq sedna. Taking advantage of the Arctic’s freshwater layers at the time, it foraged on freshwater plants otherwise absent from the sea. Soon after, it became specialised on the Azolla mats covering most of the sea, and its descendents would become increasingly adapted to a pelagic lifestyle, developing flippers, a broad snout that in derived species even lacked teeth (using keratinous plates to filter and process the soft plants) and a sealed, watertight oxygenated pouch (see below).

Iqiqquq was truly an influential animal as it prevented the Azolla Event, thus maintaing the Eocene’s hothouse conditions. But its reign was short lived, as the Arctic Ocean opened to the North Atlantic and the freshwater layers necessary for the Azolla mats could not be maintained. Further south, however, other taeniolabidids began to feed on seagrass in the Caribbean, and they soon spread across the Tethys and Pacific coastlines. Some galulatheriids also began to graze on the seagrass meadows of the Tethys, though they were not quite as common as aquatic taeniolabidids.

Meanwhile, three other mammalian lineages took to the sea. In Balkanatolia the dagontheriid kogaionids began to forage in coastoal waters as otter-like species, spreading acros the Tethys and Atlantic. They developed deep cusps/grooves on their plagiaulacoid, allowing them to both capture prey, cut meat and facultatively filter feed, essentially making them tropical analogues of leopard seals and perhaps early mysticetes. In western South America, the necrolestid dryolestoid Camahueto went from a mole or desman-like river forager to a coastoal four-flippered hunter like a mammalian pliosaur, while at the tail end of the Eocene the development of the Antarctic Ocean prompted some monotremes to take advantage of the rich circumpolar waters.

Unlike the Iqiqquq, most of these lineages were generalists and survived the Grand Coupure (albeit with heavy losses), and in the aftermath diversified. So much so, that in the Oligocene oceans marine mammals outnumbered ray finned fish at least in coastoal waters. While this may seem ridiculous, there is a precedent in Earth’s history: in the early Triassic, marine reptiles outnumbered fish and indeed occupied many niches associated with them in later eras. On at least the multituberculate side, the palinal jaw stroke was able to compete with the expanding jaws of fishes. The decline of several large fish in this timeline’s Grand Coupure while sea plants and marine invertebrates prospered made this transition to mammal-dominated waters pretty easy. That said, several small fish survived, and in pelagic environments large fish might have endured, as a ten meter long swordfish skeleton from the Chandler Bridge Formation attests.

By the Miocene, most groups became fully marine, and competed in full with the marine reptiles and sharks in terms of size. This mirrors our timeline’s own dangerous Miocene seas.

A complex niche partitioning evolved in these mammal dominated seas:

- Taeniolabidids were the dominant aquatic herbivores, grazing on seagrass meadows and kelp forests. Some species might have been opportunistic walrus-like durophagists, probing the sea bottom for invertebrates, but for the most part left these niches to other groups. They ranged from beaver to Steller’s Sea Cow size, making them the largest marine mammals of the Oligocene.

- Galulatheriids also occupied some marine grazing niches, though they weren’t quite a diverse. Some uniquely fed on corals, taking a similar ecological niche to parrotfish and thus avoiding competition with taeniolabidids. Mostly capybara to hippo size.

- Dagontheriids were mostly generalistic predators, their deeply cusped plagiaulacoids to both capture small prey, cut flesh or filter-feed, much like leopard seals. They ranged in size from otter to sperm whale, making the latter the largest mammalian carnivores of this era.

- Monotremes produced several bottom feeding durophagists like marine versions of the platypus as well as suction feeding cephalopod hunters and even a few macropredators close in size to the largest dagontheriids, but best diversified as filter feeders akin to our mysticetes (though like the early baleen whales of our timeline few exceeded six meters prior to the end of the Miocene)

- Necrolestids mostly remained porpoise sized baring a few species growing up to seven meters and freshwater taxa becoming smaller. Some remained generalistic predators, while others became durophagists specialised in molluscs and crustaceans and others still became raptorial, hunting other sea mammals and reptiles.

Hvalros tropicalis, an Oligocene marine galulatheriid known from European and Caribbean marine sites. It used its tusks to scrape off algae from corals, sometimes even eating corals thanks to its ever-growing molars. By corvarts.

These marine mammals had a number of challenges our whales, sea cows and seals did not quite have. Unlike placental mammals, multituberculates, dryolestoids and monotremes produce poorly developed young, so virtually all species were forced to come ashore at least for the young to crawl into a pouch. Several lineages developed watertight pouches oxygenated by blood vessels, a more sophisticated take on what the yapok has, but even in these species at least occasional surfacings were required. Combined with a number of species maintaining moulting pelages (though gradually replacing them with blubber by this point), this meant that most marine mammals of this timeline were tied to the coastlines, much like our seals and sea lions. DISREGARD THAT, MULTITUBERCULATES APPARENTLY GAVE BIRTH TO WELL GESTATED YOUNG. THIS MEANS THAT MARINE MAMMALS DO NOT HAVE LIMITATIONS AND SEVERAL BECAME FULLY AQUATIC AND ATTAINED LARGE SIZES.

Still, they did specialise as much as they could. Flipper like limbs were the norm, and a few lineages even began to develop tail flukes, most well developed in dagontheriids. Some developed porous bones similar to those of cetaceans, while aquatic herbivores and durophagists inversely developed pachyostic bones to help them sink better (worth noting that the earlier herbivore Iqiqquq instead had porous bones due to its pelagic floating lifestyle). External ears were pretty lost in most groups by this point, and many species developed high myoglobin concentrations to allow maximum oxygen carrying capacity without needing to expand the lungs, a condition seen both in marine mammals as well as mammals that evolved from them. No species developed echolocation, but vibrissae and in the case of monotremes electroreception became excellent aids to vision in darker waters.

Illyriolestes piscimimus, a freshwater dryolestoid from european waterways during the Oligocene. By lizardsaurus.

While the expansion of cetaceans and seals is often blamed for the extinction of giant penguins and plotopterids, neither group declined in spite of the spread of marine mammals in this timeline.

Several lineages returned to freshwater biomes, much like countless other species from river dolphins to freshwater plesiosaurs. Taeniolabidids and dagontheriids did this the most, the former occupying freshwater herbivore niches so efficiently as to discourage terrestrial herbivores like sudamericids and adalatheriids to pursue even semi-aquatic niches, while the latter suppressed the evolution of most other otter-like mammals aside from some eucosmodontids. In some island environments like the Caribbean taeniolabidids returned to a mostly terrestrial lifestyle in the absence of competitors, but other marine mammals had less success returning to land, perhaps due to being specialised for aquatic prey.

Leave a comment